Traditional and Indigenous building methods in Colombia reveal how construction is an intimate engagement with other species, the work they do, and the very core of our planet.

Home. I think about it every day.

What is housed in the word home?

Home is, to me, a diffuse and overarching idea that I come back to on a daily basis. I have moved around throughout my life escaping it, embracing it, analyzing it, ignoring it. Home is always there. And as an idea it is one that I have written about explicitly, like in my “Oikos,” or through most of my work, asking what home, place, and identity mean to different people. Home can be a casing. A category. A structure. A framework. Like the cell that houses a nucleus. Like the body that houses sentience. Like the page that houses sentences.

So because of all of these examples, I also wondered about literal homes. The places we inhabit and the materials we use to make them our own.

We seek a home when we lose it. Asylum, refuge, sanctuary, and shelter … all of them have a Familienähnlichkeit: All of them are related, then again, all of them are different. Each is nuanced. Each is one more way of housing with a different purpose: political, social, religious, and so on. But at the same time, they reflect or refract aspects of each other, all still providing a home––and that’s the through-line.

How do we provide homes? How do we learn to build homes? From those that came before us. Our parents, their parents, and their ancestors. From their life, from their example. Or from their victories and failures.

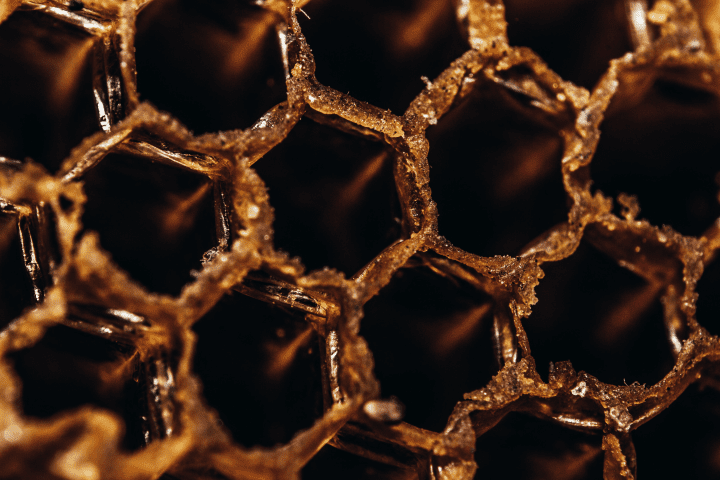

But before we were even Homo sapiens, who learned to build a home with nature first? Dinosaurs building mud nests or shaping a burrow and burying their eggs? Wasps building paper nests? Fish clearing hollows in the seafloor? Does it matter? The important thing from all these questions is not who was first. Or who’s best. Or who’s evolved more biologically and neurologically to be the most efficient at it. Or to do what’s new.

What’s vital is to recognize we’re part of a continuum of homemaking and homebuilding entities, learning to keep up with ourselves and to find ways of housing who we are and who and what we care about through the creation of structures and frameworks that can make us be comforted and comfortable. It’s simple, really, to see ancestral techniques of human homemaking gravitating then to the origin. To nature. And to use materials that are from nature with nature, to help us create circular processes that diminish energetic expenses, where less CO2 is produced, and the temperature inside of our homes adapts to the outside.

In my quest to keep thinking about home, I found myself in Santander, Colombia in 2022. This is the place where both of my grandmothers are originally from. While I was on a reporting trip there, an idea came to mind as soon as I looked outside my window. These houses around here in Santander are homes also because of how we built them. The main techniques used? Let’s start with tapia pisada, coming from the Spanish colonizers and bahareque, inherited from the Indigenous peoples.

The first, tapia pisada, uses mud, soil with water, and gets compacted by the weight of the person creating it. Hence, the tapia is “pisada,” stepped on. More closely compared to cob house making, or tabby concrete, in the United States of America. And the second one, bahareque, uses wood and soil to build. Where did these two techniques come from? I spoke with Santiago Rivero Bolaños, a civil engineer, and with his wife, Lina Pieruccini, who lead a project called De la Tierra Casa Taller in Barichara, Santander. Santiago told me that, to him, using these techniques to build homes could have come from the necessity of hominids to give themselves a roof, a shelter, made from their own hands, and adapting their resources in their environment to create a pleasant place. To look at nature, to see the home it provides, and to learn one of its aspects to apply it to our own natures, fashioning tools and creating structures like what we see in other natural phenomena. This is part of what is termed as and . To see what nature does and imitate it and to find a framework and fit that biological material into it. Like the biological materials in soil and wood in these two techniques.

And the thing about those two is that in one you’ll see geologic time and the layers embedded in and existing in the crevices of the soil. In the other you’ll also see all the nutrients and ways in which these trees interacted and grew. Nature is not only what is alive or has the characteristics of life. Nature is also found in the interactions of life and death. See: thermodynamics. Of what interconnects with trees in the soil. Santiago echoes this to me:

Soil is a complex material with different shades to be observed in it. There’s life and death at the same time. Organic and inorganic matter. And that’s our planet and our universe too. And these materials remind us of death not as cessation but transformation of matter reintegrating into itself.

This soil is a hyperobject, an incalculable mass of bioproducts, rocks, sand, water, and layers upon layers of life that has existed and will keep nourishing the life that will continue to exist. But what lives in the soil? Or what uses the soil as its home? Bacteria, microorganisms, insects, roots, worms, animals and other organic matter in decomposition. And all this natural occurring material is an integral part of the walls that Santiago and his wife make with tapia pisada.

These walls are the fractal of information that tells us how elemental is our planet, how elemental is our universe, following a continuous transformation that in its organic and inorganic matter is spontaneous, intuitive and miraculous too.

When I asked Santiago how to know what is the exact point of humidity that is necessary for the mud mixture to become compact enough that it would become resistant, he told me an anecdote. When he was still in university, he consulted a maestro tapiero who would use his hand molding the mixture to find the humidity point. This biomimetic way is as good, or even better, than a more post-modern and post-industrial way of creating bricks. Relying on what has been taught before, in the actual and literal manipulation with our hands, we rely on our senses and our memory. We rely on an elder’s examples, we rely on mimicking our ancestors, their traditions and their techniques.

Santiago wanted to test the biomimetic technique versus a lab proctor test. And at his university’s lab, he tested out the humidity of the tapia from a proctor test. And comparing it with the ancestral technique from the maestro, he would find that both techniques would have the same compactness. That is when Santiago realized something about the ancestral technique versus the newer technologies:

Formulas and cartesian planes, curves and algorithm driven software, all of them are only a way of interpreting the universe around us.

To liken something, to mimic it, to use it and reuse it. These all are part of what the building techniques known as tapia pisada and bahareque are. And like natural materials and the majority of other biomimetic resources, these techniques are reversible. By this we are also talking about research done by Ilya Prigogine and Isabelle Stengers to understand chaos and what is actually irreversible in nature. Industrial materials, Santiago notes, are created with irreversible physico-chemical processes that, “if I were to call them something from a more mystical perspective, they are dead materials.” But tapia? Bahareque? These are reversible, they reintegrate to the system that brought them together. And, as they come from nature, they also are nature embodied. Like we are too.

Sounds of the Soils

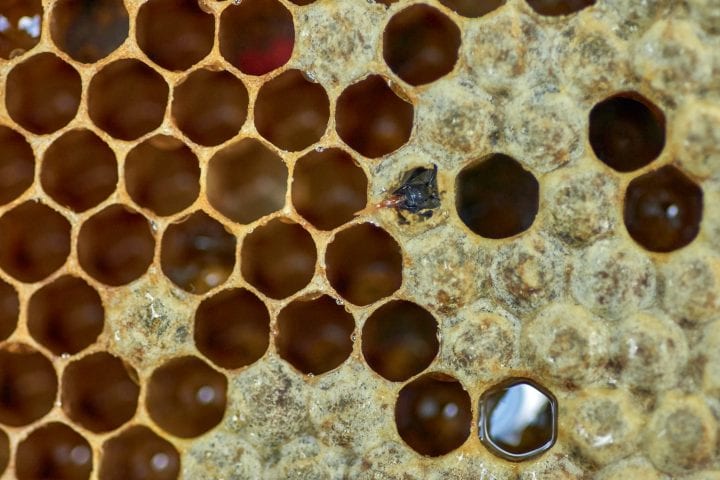

You heard them now too. You see them as well. These are the soils used to build with tapia pisada and found in different parts of the Departamento de Santander, Colombia. Each one has a different color, texture, and sound. Some of the soils from Santander that are showcased come from Jordán, San Gil, Villanueva, Mogotes, Barichara, Aratoca, Guane, Curití, and Lebrija. Guane, the town, is named like that in honor of the Indigenous peoples of this part of what is known now as Colombia who used to eat hormigas culonas, as I reported recently. These leafcutter ants in Santander have built their underground homes, caring for fungi in a complex agricultural system that has endured from before the dinosaurs until today, in which they domesticated fungi and created their own underground homes. Other organisms, living and non-living things are part of these elements of these living houses, like in Disney’s Encanto. Houses that are alive in the way that we cohabitate in them with natural elements that coexist and relate to us in different times. Here’s Lina explaining what she means by that:

Soil doesn’t only let us harvest from it, but also to walk it, to build homes with it. And whoever lives inside of a living house like this one we’re in right now, knows how [the house] lives with you, teaches you, speaks in a way with you.

The tapiero master and the counter-pisón, [the other person building] are the ones who are dancing inside the wall that is being created. They must both be careful with each other’s feet in order to not step on each other, but also to step as if they were creating music out of their construction. It’s no reggaeton or vallenato, it just simply is sound of the earth that is being stepped on. And when a certain point is reached, a dry sound is generated. There is a change from the first sound that they start with. So those changes in sound from these tapia structures are simply part of that tradition and all that magic that surrounds this type of construction.

Like the saying, “nadie te quita lo bailado.” No one can take away what you’ve danced. Or built.

Sounds of the Tapiero Master at Work

Near where Santiago and Lina live, in a more rural area of Barichara, I spoke to Ramón Atuesta. He is a campesino from the Guayabal path keeping the Spanish and Indigenous building techniques alive as well as other gastronomical traditions. Tapia, he recounts to me, has been around for more than 317 years in Barichara. Older than Colombia as a republic itself. Barichara, he also notes, has 732 houses made with a repetitive and persistent pattern of building: tapia pisada. He attributes its staying power to geometry, volume, and compacting. The third, he confirms independently from Santiago, is something that cannot be standardized but can only be passed down. The compacting with your hand has to be learned from an elder. To build a home we need to learn from those who came before us. To create a home we need to learn what has worked in the past as well as what can destroy it.

Ramón also built a ceiling with about 12,000 older tiles collected from Girón, Piedecuesta, Tunja, Moniquirá, San José de Pare, among others, because he wanted to honor his ancestors and reuse these bricks to continue building with them.

Speaking of learning from our elders in this way, I spoke to Santino “Tino” Gonzales, a collaborator and friend of mine, who is also an artist originally from Los Lunas, New Mexico.

Los Lunas is one of the places in the U.S. where another technique, adobe, is very common. Tino loves adobe. I spoke with him as soon as I got back to Oakland, California, a place which we have chosen as our home. Tino is at the crux of three things from his hometown: adobe earth building, ufology, and radio technologies, and in his artistic practice you see the three interacting all at once. Crossing into third-spaces, into in-betweens, into limbos. Like the “adobe summer” from his 2020 album “Bookfair,” recorded in the summer of 2019.

This was amidst Tino reconnecting with his dad and asking him about if he had ever worked with adobe, as adobe is everywhere in Los Lunas, including the first place Tino ever found himself with it: San Clemente Church. He asked his dad if he knew how to make adobe bricks, and after his father told him stories about learning to do so as a nine-year old and earning money as a young adult, he said he would be happy to teach Tino. Since then, Tino has incorporated adobe into his artistic practice and as a meditation on his own life and heritage.

And then after I kind of just kind of began cranking them out over like a two week period. I was just making an ton of bricks with no real aim or real goal. I wasn’t trying to make a structure. I would just wake up in the morning and go do this thing. And it just became like a really great way for me to talk about the things I was trying to talk about in my artwork, and which are oftentimes about themes like connection and relating to ideas about home and the unknown. It contains all this information, and that’s something that I’ve carried with me. This adobe brick is also who we are, a culmination of mestizo heritage, of mixed techniques.

And that is also what draws me to these techniques. That in our messy mestizaje, our ancestors found value in building homes like this. There is a real materiality that comes from using something that is alive and creating something with it to endure. If treated right, and maintained, adobe can even be fire resistant. A resilient block that like tapia and bahareque, are variations on a theme. They persist and insist. And that is also, the “from dust you come and to dust you shall return” nature of them, that draws Tino to them as well. Because you have to give them attention and care.

It’s an ongoing living thing. It’s something that needs to be tended to. It’s something that has a long shelf life. It can survive for hundreds of years, when taken care of. They are alive and they also require attention and care.

If culture is what we care about, the culture of homemaking with these techniques––adobe, bahareque, and tapia pisada––is one of our oldest forms of culture with rupestrian art and oral storytelling. These things help us layer our relationships, our building structures, with limits, with frontiers.

And these bricks and materials are witnesses to our histories. But as Tino also told me: they also have been participants.

[Adobe] has already outlived us. It goes into deep time and it also is going to extend beyond our own time. And hopefully it’s like a hard drive, and you plug it into your computer and you have access to all this information. And I think, in the same way, the brick is a container of history, of information, and of knowledge that is passed down. And that’s why I really love it. Because it was like a way for me to connect, not only with my father, but to his father, whom he also learned how to make bricks from. There’s that dialogue, that kind of historical dialogue between our families and that’s a way for me to talk with my father—and onward.

With an industrial brick, a tool that has been useful in creating what we want to create, we have a machine or a series of industrialized processes to end up with a product. A product, that while it has the hands of humans throughout it, or ending with it, loses its natural elements. With the natural brick created with the adobe technique, the soil conserves more of the organic elements that were featured to create it in the first place.

And this adobe brick, the basic element used, has a history too. And the brick is both the story being told, as well as the element we use to tell the story with.

Language fails, words are not enough. But the brick hums things and reveals things that sensitive eyes will only be able to see.

It’s simple, really, to see the benefits of returning to a mindset that lets us use materials that are from nature with nature. To better help us create a series of circular processes.

Are these materials ideal? Can they be completely seismic-resistant? Not fully. And like a lot of other structures, they will eventually fall.

But they also have endured for longer than the industrial ones we use these days.

How to build and combat the enemy within the home, our own egos, when all that’s left to do is up to us? I think we ought to keep playing with soil, remembering where we come from, and where we shall return. And with that soil, with that wood, with that material—build. Brick by brick, reconnecting with what and who made the bricks in the first place.

That’s how we’ll continue transforming with and living in our only home: Earth.

Camilo Garzón is an award-winning Colombian-American poet, writer, filmmaker, interdisciplinary artist, voice and creative director, oral historian, and educator, as well as the founder of Cuentero Productions. His extensive journalism and multimedia work has been featured in major outlets like Scientific American, NPR (including All Things Considered, Morning Edition, and TED Radio Hour), and the National Geographic Society. Since early 2022, his projects have continued to garner recognition, including a Webby Award nomination for The Mission Muralismo Audio Zine – Volume I, a Tribeca Audio Fiction Storytelling Award for The Very Worst Thing That Could Possibly Happen, and the recent co-writing and co-production of the short-documentary sports film JUNIOR TU PAPÁ, which premiered at the True/False Film Festival. Camilo also serves as the AskNature program director at the Biomimicry Institute. Follow him on Twitter @CamiloAGarzonC and Instagram @Camilo.A.Garzon.C.

The Collection

Explore some of the incredible ways other species work with mud, soil, and wood to construct their own homes, communities, and other structures.