Ballistospores of fungi are catapulted away by coalescence of water droplets.

Fungal spores are tiny particles that perform a similar function to seeds in plants. Spores are usually single-celled and can grow into a new organism without requiring fertilization. Like plants, fungi need to disperse their spores in order to colonize new locations. Spores are very light and can be carried large distances by air currents. However, fungal fruiting bodies from which spores are dispersed are small and usually grow in low sheltered spots. In order to reach air currents, fungi distribute spores in a number of different ways. Some rely on wind or rain droplets to dislodge spores, while others, such as Pilobolus, are capable of shooting their spores distances of up to 2.5 meters.

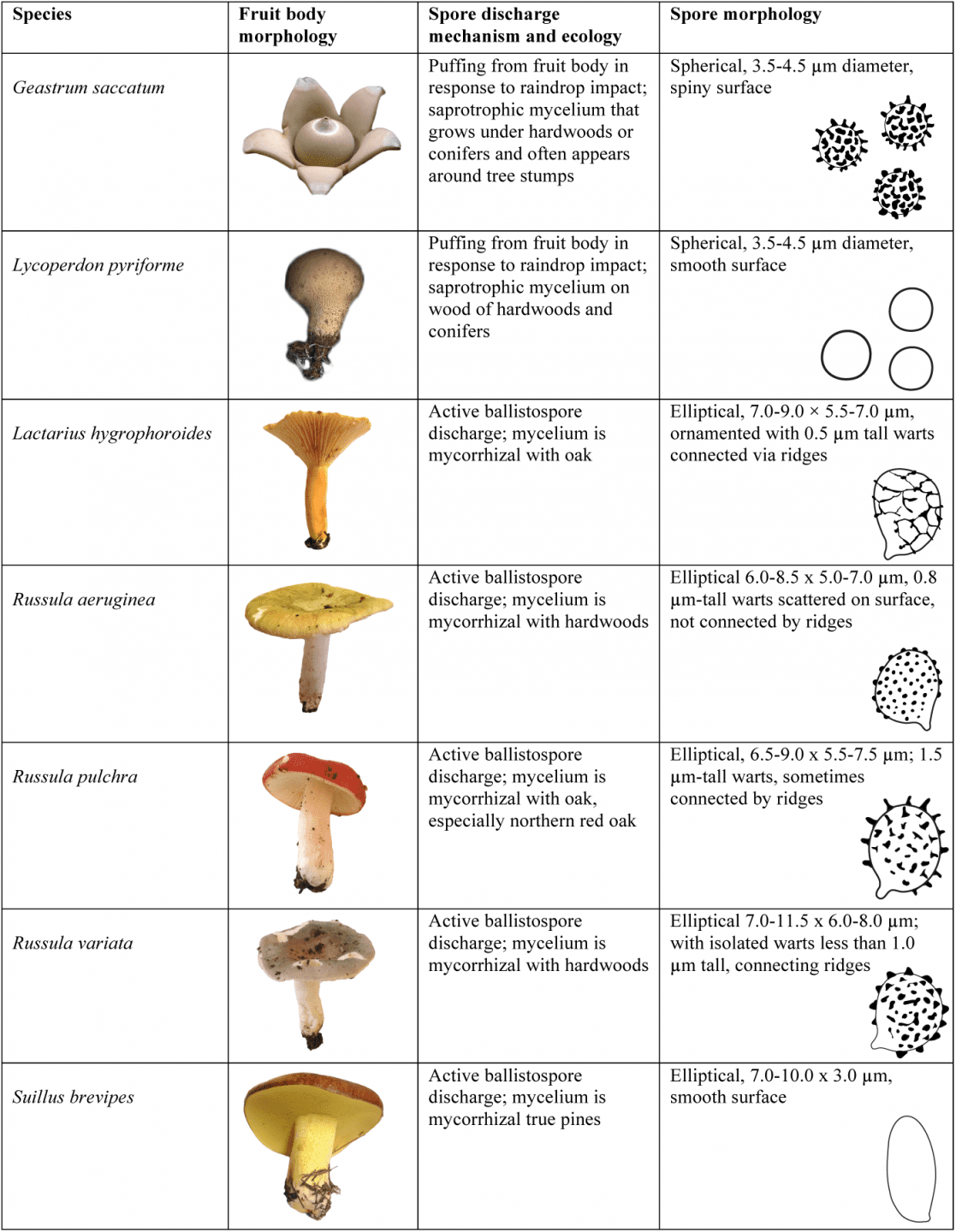

The Basidiomycota are one large sub-division of the kingdom Fungi, comprising more than 30,000 known species. Basidiomycota have diverse methods for dispersing spores and one common mechanism is a ballistospore. Ballistospores are crescent shaped single spores that grow from the tips of specialized spore-producing structures called sterigma. Once mature, ballistospores spontaneous launch from the fruiting body at velocities of 1.2 metres per second, achieving 12000 g.

The mechanism of ballistospore launch is passive and makes use of air humidity and the natural behavior of water. Each ballistospore has two hygroscopic (water absorbing) patches on its surface. The patches are coated with sugars, including mannitol, that absorb water from the air and guide formation of two droplets on the spore’s surface. The patches are separated by a hydrophobic strip that prevents the drops from merging until they reach a critical size. Once they are large enough, the two drops make contact and merge. This merging causes the water to spread over the surface of the spore, changing its center of gravity and releasing energy from the altered water surface tension. The energy from the moving water enables the ballistospores to “jump” off the sterigma.

Fungi produce countless spores and, in an interesting addendum, ballistospores may have a far wider impact than simple fungal reproduction. After launch, the thin layer of water quickly evaporates, leaving the mannitol that had been concentrated in two precise locations spread over the entire surface of the spore. The fungi that produce ballistospores live primarily in forests, and this means the air above forests contains large numbers of aerial ballistospores. The mannitol coating the spore surface maintains its hygroscopic nature and continues to absorb moisture from the atmosphere over the trees. One theory suggests that this action could seed cloud formation and lead to increased rainfall over densely wooded areas.