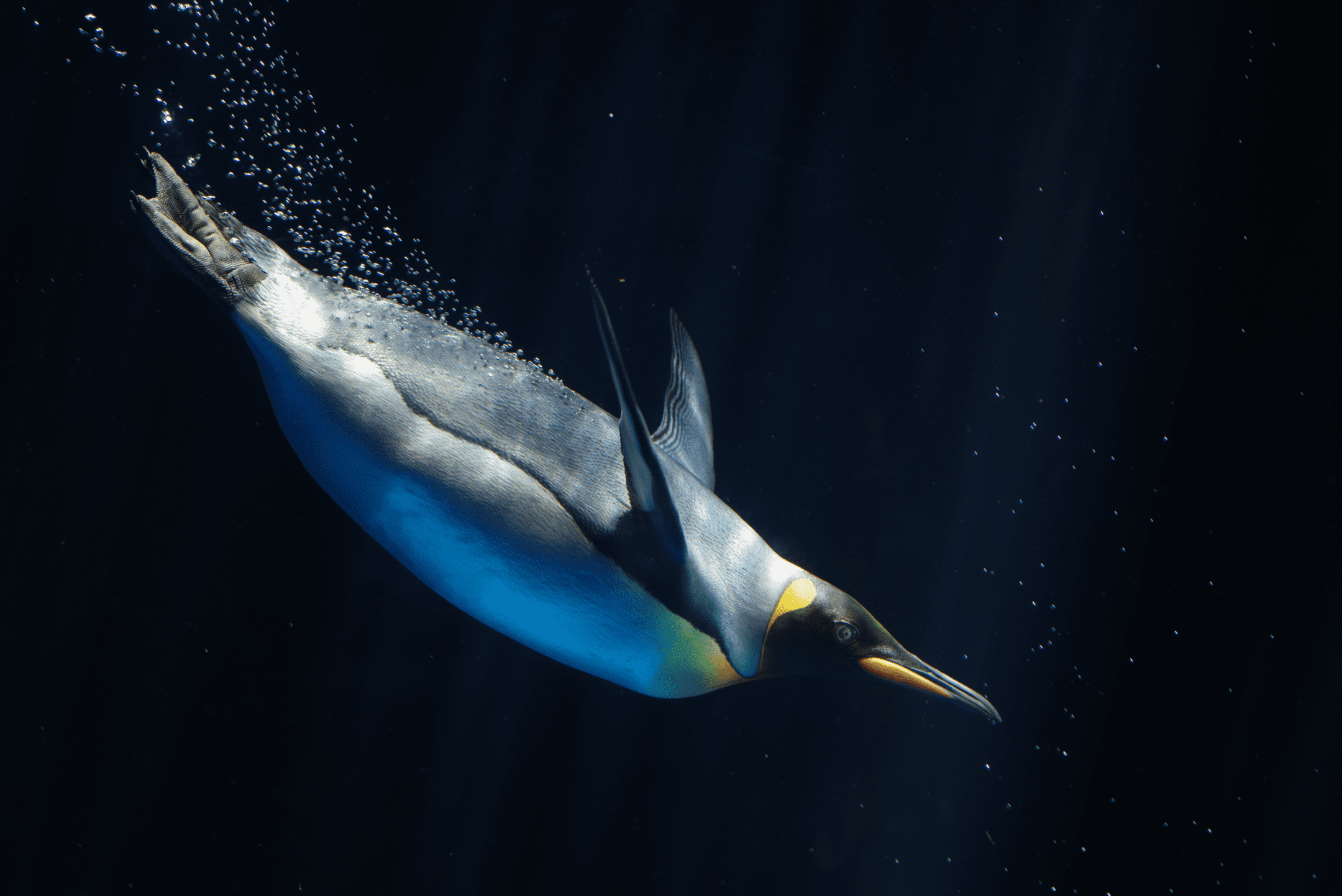

The feathers of penguins prevent water from penetrating to the skin due to their stiff, tightly packed structure.

“The penguins (below) lost the power of flight some 100 million years ago, and have no flight feathers on their wings. Their stiff close-packed feathers form a thick insulating mat that is impervious to water and provides a good streamlined surface for swimming.” (Foy and Oxford Scientific Films 1982:111)

“Several studies have investigated the thermal resistance of penguin ‘coats’ (feather and skin assembly) and found it to be surprisingly low—an average of 0.74 m2KW-1 or 7.4 Tog. Penguin feathers are heavily modified, being short (30-40 mm), stiff and lance shaped. Insulation is provided by a long (20-30 mm) afterfeather. Penguins are unique in that the feathers are evenly packed over the surface of the body (30-40 per cm2) rather than arranged in tracts. For insulation the penguin requires a thick, air-filled, windproof coat (similar to an open-cell foam covered with a windproof layer) that eliminates convection and reduces radiative and convective heat losses to a minimum. However, when diving, the penguin requires a thin, smooth and waterproof coat with no trapped air (positive buoyancy would be a big disadvantage to an active swimming hunter). It achieves this by using muscles attached to the shaft of the feather to ‘lock down’ the feathers to create a water-tight barrier. In addition, the feather rachis is flattened dorso-ventrally allowing it to bend and conform to the body shape readily with increasing water pressure.” (Dawson et al. 1999:199)