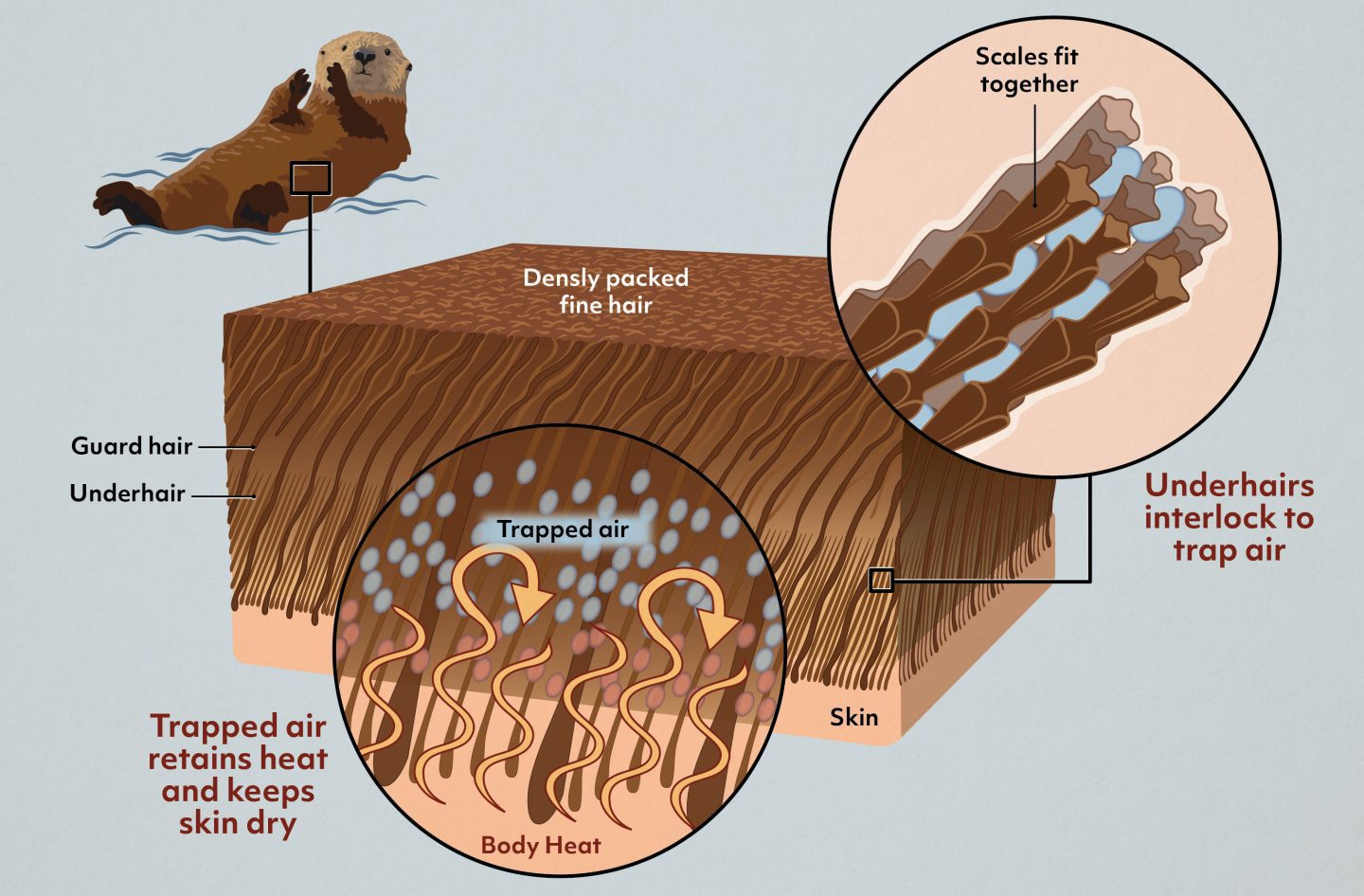

Long scales on the underhair of otters and fur seals trap air to retain heat and prevent water penetration.

Introduction

Many aquatic mammals face a serious physical challenge: they must stay warm while spending significant periods of time in extremely cold waters. Sea lions, walruses, and true seals have thick layers of blubber to keep them warm, while fur seals have much thinner layers, and otters do not have any blubber at all. Instead, fur seals and otters rely on very specialized layers of hair to maintain their body temperature in and out of the water.

The Strategy

The pelts of all fur-bearing animals—whether they live on land or in the water—are actually made up of two different types of hair that grow in clusters together: guard hairs and underhairs. Underhairs are shorter and denser, with three or more underhairs growing in a follicle for every one guard hair. Guard hairs are longer, and usually extend out over the surrounding underhairs, creating a protective canopy for them.

Studies have shown that aquatic mammals relying on fur for insulation have scales on the cuticle (outer layer) of their underhair that are more elongated compared to aquatic mammals that rely more on blubber. The protruding of the scales causes the hairs to interlock, preventing the penetration of water, and also trapping air bubbles. Air is a poor conductor of heat, so the bubbles provide an insulating layer, preventing heat loss from the animal’s body.

Scientists also noticed that fur-bearing marine carnivores have significantly flatter and denser hair than carnivores found on land, such as bobcats and ermines. They performed a test of the different pelt types, putting fur samples from each in a small pressure chamber, covering them with water, and then observing how far the water penetrated into the fur when subjected to increasing pressure. The marine carnivores’ pelts were far better at blocking out water and maintaining the layer of air within the fur, providing evidence that flatter, denser hair was an that helped mammals survive in aquatic environments.

Scientists also noticed that fur-bearing marine carnivores have significantly flatter and denser hair than carnivores found on land, such as bobcats and ermines. They performed a test of the different pelt types, putting fur samples from each in a small pressure chamber, covering them with water, and then observing how far the water penetrated into the fur when subjected to increasing pressure. The marine carnivores’ pelts were far better at blocking out water and maintaining the layer of air within the fur, providing evidence that flatter, denser hair was an adaptation that helped mammals survive in cold aquatic environments. In fact, sea otters, followed by fur seals, have the densest fur of all mammals.

The Potential

Understanding how fur keeps aquatic mammals warm could inform the development of insulation and clothing for wet environments and, in particular, for situations where people or objects are moving frequently into and out of water.