Coordinate by Self-Organization

To create and maintain a healthy community of individuals and ecosystems requires that living systems coordinate their activities. Coordination doesn’t necessarily mean that there’s a leader orchestrating what happens. In nature, coordination is usually achieved through self-organization. In a flock of geese flying in a V-formation, for example, there’s no lead goose controlling where all of the others fly. The flock uses this formation because each goose gains energy from air vortices created by the goose in front of it. The lead goose doesn’t gain that benefit, so when it tires, it moves back and another goose takes the front position.

Respond to Signals

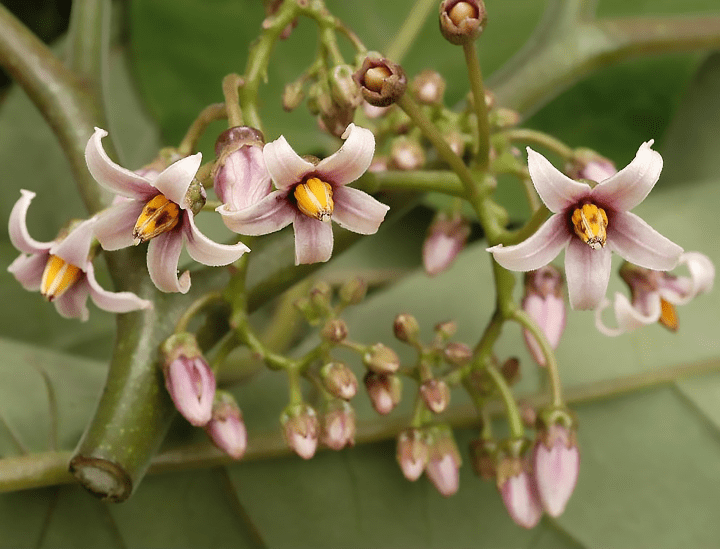

To interact with its environment, a living system must not only sense a variety of signals, but also respond to them. To be energy- and material-efficient, those responses must be appropriate to the signal. This generally requires sensing thresholds to trigger an appropriate level of response (for example, hiding under a shrub versus running away to avoid a predator). Response strategies are tied to a specific signal and often have a response threshold, which determines how strong a signal must be to warrant expending energy to respond. One example is a plant that lives in arid regions in South Africa. Its seed capsules remain closed until rainfall triggers them to open to release the seeds. But the plant only responds to a second rainfall, thus protecting against releasing its seeds before there is enough sustained water for them to grow.

Navigate Through Liquid

Living systems that move in liquids must navigate around physical obstacles and find their way from place to place to locate resources or suitable climates. Many liquids are denser than air, which means it’s a thicker medium through which signals must pass. On the other hand, liquids tend to conduct some signals better than air or solids. Liquid dwellers must use strategies that enable them to detect and follow signals in this dense medium. For example, electricity transmits well in water and several organisms, such as Amazon electric eels, have organs that detect and use electric signals to navigate.