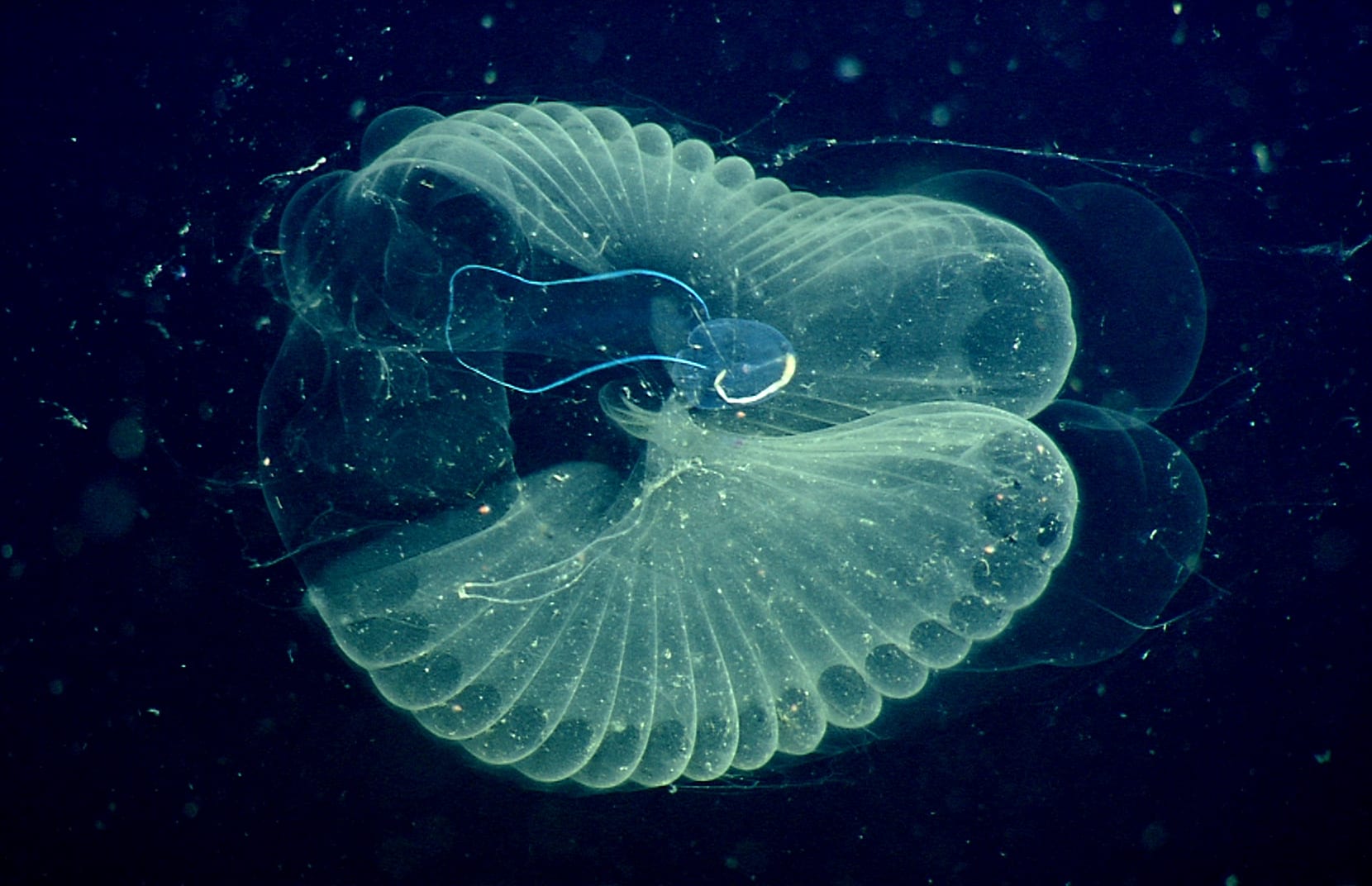

The mucus “houses” of the giant larvacean enable it to filter seawater and sequester carbon in the ocean more efficiently than any other zooplankton.

Introduction

The tiny oceanic creatures called giant larvaceans are “giant” only in comparison to their relatives. New research shows these strange invertebrates have the greatest capacity for filtering seawater of any zooplankton, and so may play an important role in trapping carbon and keeping it from reaching the atmosphere.

Zooplankton (from the Greek for “drifting animals”) are generally microscopic waterborne organisms that feed on phytoplankton (“drifting plants”). Larvaceans specifically are simple creatures, consisting of a head (or trunk) and tail, somewhat resembling tadpoles.

The Strategy

What aren’t simple are their feeding structures––complex filters called “houses” made of mucus that extend far past the body. For most 2-8mm larvacean species, these “houses” can range from 4 to 38 mm (up to 1.5 inches) in diameter, but for the giants of the family, like the Bathochordaeus seen below at 3 to 10 cm (1 to 4 inches), the filtering structures can reach a meter (39 inches) in width. It’s this house structure that enables giant larvaceans to do such an efficient job straining sea water for their tiny food. The wide-meshed outer parts of the filter keep out anything too big to consume, and a smaller inner filter funnels food particles to the mouth via a tube. It’s all powered by the constant motion of the animal’s tail directing water inside and through the house.

Like all filters, the giant larvacean’s house eventually gets clogged with particles. When this happens, as often as once a day, the animal discards it––and that’s when the species’ contribution to carbon sequestration becomes apparent.

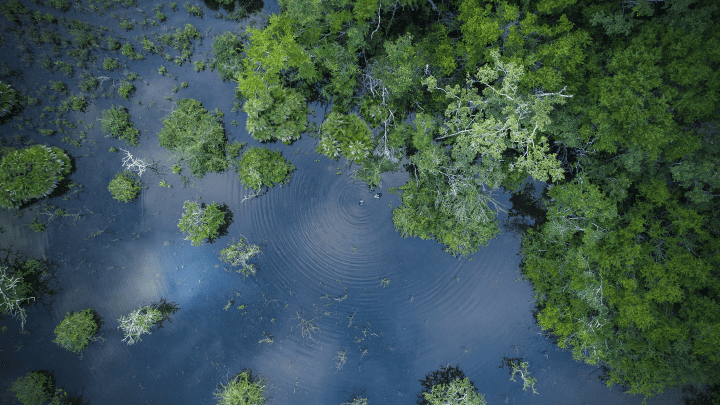

As organic structures, the houses are full of nutrients, most relevantly carbon. Once abandoned, they sink down to the bottom of the sea, where their carbon can stay sequestered, or excluded from going back into the atmosphere, for thousands or millions of years. Because larvacean filters are relatively large and heavy, they sink more rapidly than smaller organic particles, giving them little time to degrade in the upper ocean where their carbon would be more likely to enter the atmosphere as CO2.

The Potential

Understanding how giant larvaceans build such efficient filters, and how they do it so quickly, is a promising area of study. As our understanding of them improves, these amazing structures could inspire designs for new filters and expandable structures, perhaps even opening the doors for easier or more sustained deep-water or space exploration.