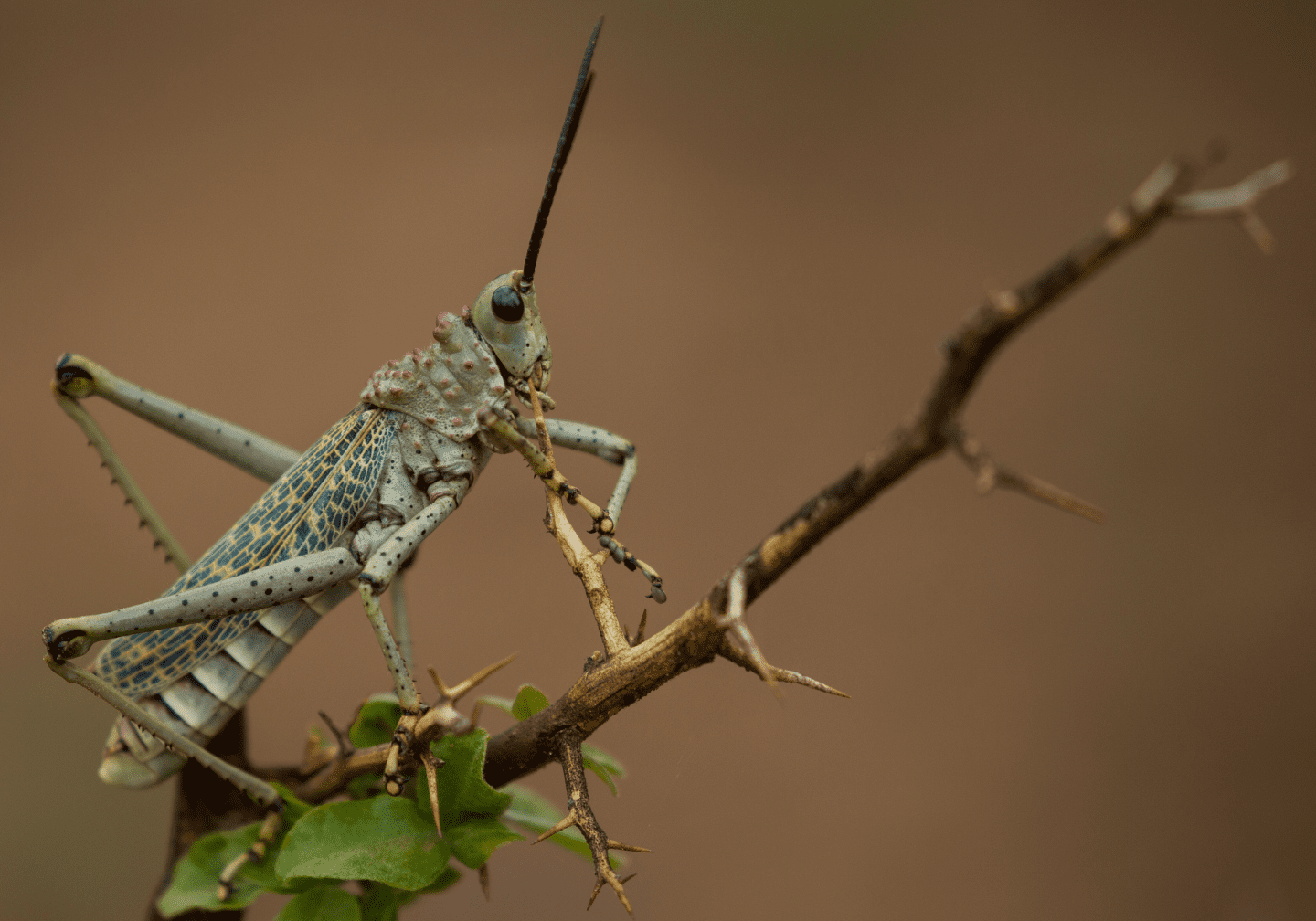

Swarming locusts eat toxic plants and change color as a warning to predators.

Introduction

Swarming locusts bouncing into each other might seem like a strange comparison for humans. The locusts’ response to such contact though presents an intriguing model for us to consider.

The key points are that locusts use changes in population density to trigger major changes in their behavior and activity, and they announce loudly and clearly that those changes have occurred.

The Strategy

The physical touch from other locusts detected by the hind legs, or simply the sight and smell of other locusts nearby can trigger a release of serotonin that makes a normally loner locust drawn to living closely with many others of the same species.

But this is not the only change the locusts undergo when swarming. They also slow down their ability to learn to dislike certain foods, and they “forget” their earlier aversion to them. What this means is they no longer avoid toxic plants, and instead begin to consume them. The locusts themselves still suffer from a toxic malaise, but more importantly it makes them toxic to consume.

This toxicity is related to a change in appearance as well. When living as individuals, desert locusts are green or brown and blend in with their surroundings, avoiding being eaten by avoiding being seen. Once they travel conspicuously in giant swarms, they change the production of red pigment, causing their existing colors and patterns to appear much more vibrant and striking. This signals to predators that eating this abundant new food source will actually be harmful––especially if eaten in high quantities.

This content marked as “Google Youtube” uses cookies that you chose to keep disabled. Click here to open your preferences and accept cookies..

The Potential

We can learn a lot from this example in nature when considering potential interactions between humans, machines, or humans and the machines we build. Sensory inputs could trigger changes to behavior that allow robots to be more positively received by humans when around them, but more optimized for performance when alone. Following the locusts’ lead, this change of behavior and intent can also be communicated outwardly through physical appearance, so that the humans know that the robot is now operating under different instructions.

Related Content

AI on AskNature

This page was produced in part with the assistance of AI, which is allowing us to greatly expand the volume of content available on AskNature. All of the content has been reviewed for accuracy and appropriateness by human editors. To provide feedback or to get involved with the project, contact us.