Spores that form in Bacillus type bacteria provide dormancy at high temperature because enzyme proteins change shape as the spore dehydrates.

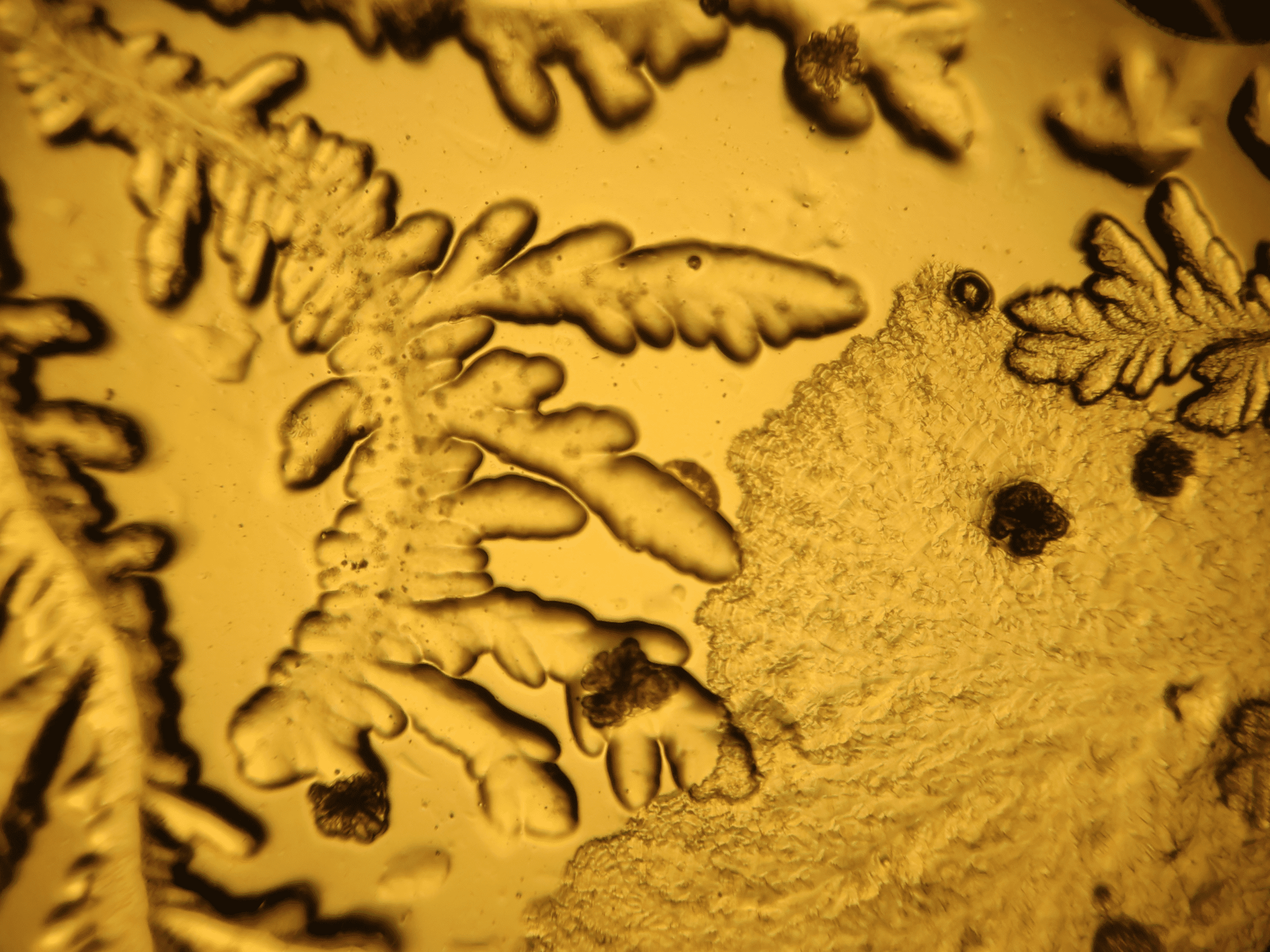

Can relaxation make you tougher? Yes, research shows, if you are a bacterial endospore (also simply referred to as a “spore”). Endospores are tough dormant structures that form inside the cell wall of certain types of bacteria, such as Bacillus bacteria. These tough capsules form in response to adverse conditions such as drought or high temperatures. They are also resistant to ultraviolet radiation, desiccation, extreme freezing, and chemical disinfectants. Analysis of enzyme structures within endospores suggests that reversible relaxation of their three-dimensional structure is the strategy Bacillus bacteria use to survive at temperatures deadly to non-spore forming cells.

When exposed to higher temperatures, such as that of boiling water, the internal bonds of the bacteria’s folded enzyme relax to form long chains of molecules. These chains move about freely in the low water content of an endospore’s core region. Since the functional enzyme shape has relaxed, the cell machinery stops and the dormant state associated with the endospore is the result. When cell temperature becomes more hospitable, the protein chains refold back into the the normal enzyme structure. At this point, the cell returns to normal functioning.

Bertil Halle, the lead scientist for this study, sums up the connection between partial dehydration, increased temperatures, and dormancy in Bacillus bacterial endospores by stating, “‘What we have discovered is that the water in the spore is nearly as fluid as in regular bacteria, while the enzymes are largely immobile. We therefore think that spores’ heat resistance and ability to shut down their cell machinery can be ascribed to the fact that certain critical enzymes do not function in the low water content in the spore core. But much more work is needed to figure out the details of the mechanism.’” (Viegas 2009)

This summary was contributed by Sue White.