The skin of cuttlefish changes color rapidly by expanding or contracting elastic pigment sacs.

Introduction

The idea of turning invisible is so intriguing to us humans that every generation invents new superheroes and villains with this ability in the stories we tell. But it’s not really fiction. In the real world, cephalopods such as cuttlefish can use dynamic camouflage to blend in with their surroundings on demand. No matter the background, in a matter of seconds, poof, they’re gone.

The Strategy

Cuttlefish are able to match colors and surface textures of their surrounding environments by adjusting the and iridescence of their skin, which is composed of several layers.

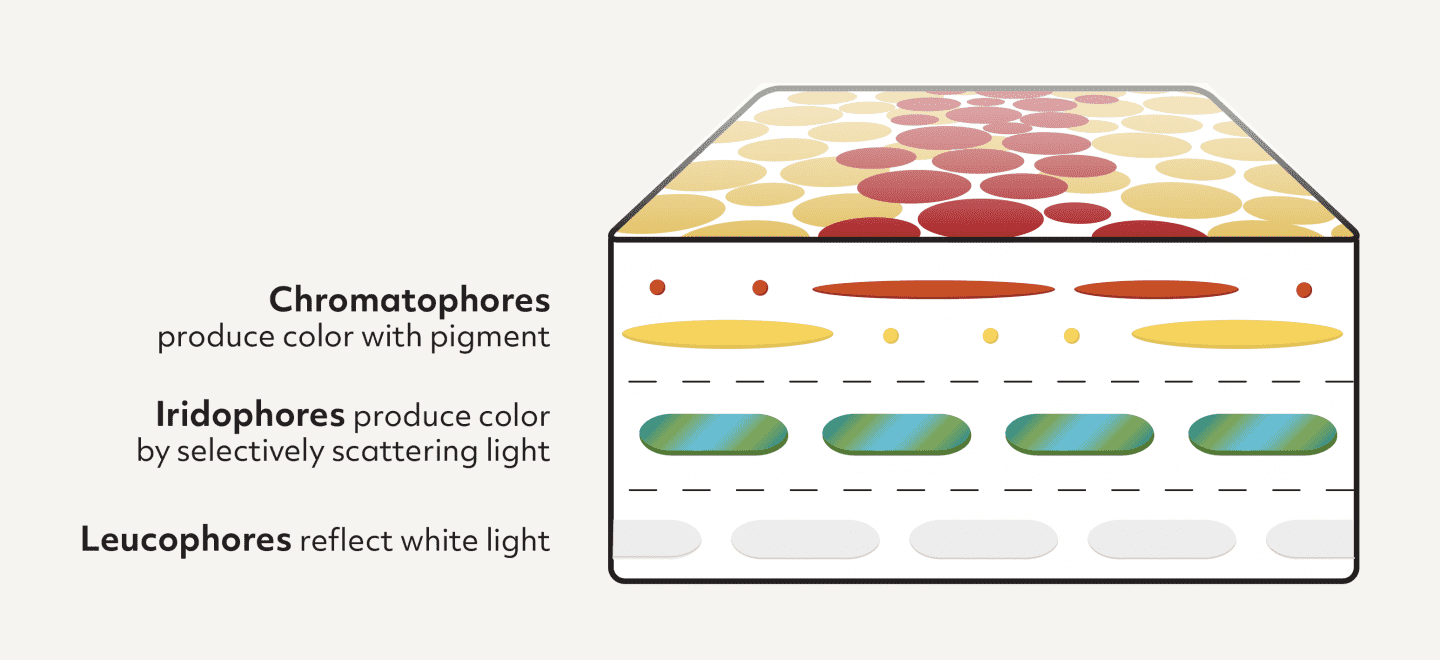

On the skin surface, chromatophores (tiny sacs filled with red, yellow, or brown pigment) absorb light of various wavelengths. Once visual input is processed, the cephalopod sends a signal to a nerve fiber, which is connected to a muscle. That muscle relaxes and contracts to change the size and shape of the chromatophore. Each color chromatophore is controlled by a different nerve, and when the attached muscle contracts, it flattens and stretches the pigment sack outward, expanding the color on the skin. When that muscle relaxes, the chromatophore closes back up, and the color disappears. As many as two hundred of these may fill a patch of skin the size of a pencil eraser, like a shimmering pixel display.

The innermost layer of skin, composed of leucophores, reflects ambient light. These broadband light reflectors give the cephalopods a ‘base coat’ that helps them match the brightness of their surroundings.

Between the colorful chromatophores and the light-scattering leucophores is a reflective layer of skin made up of iridophores. Iridophores use structure to reflect incoming light, to take advantage of other colors provided by the environment. Iridophores selectively reflect light to create pink, yellow, green, blue, or silver coloration.

The combination of these skin layers allows cephalopods like the cuttlefish to blend in quickly with virtually any background.

Watch this video from PBS Deep Look to learn more about how cephalopods use adaptive camouflage:

The Potential

Technologies which control how much an object stands out or blends in have many different potential applications. “Smart” crosswalks, for example, could help to make crossing pedestrians more obvious to drivers and self-driving vehicles, and a truly smart phone being sought by its owner could change its color to contrast with the couch cushions it’s tucked between. The chromatophores of cuttlefish also give us the idea of materials that change colors with force or bending. This could be very helpful in everything from visual indicators of car tires getting low on air, to structural elements of bridges deforming and indicating they’re in need of repair.