Salt tolerance evolved differently across plant species

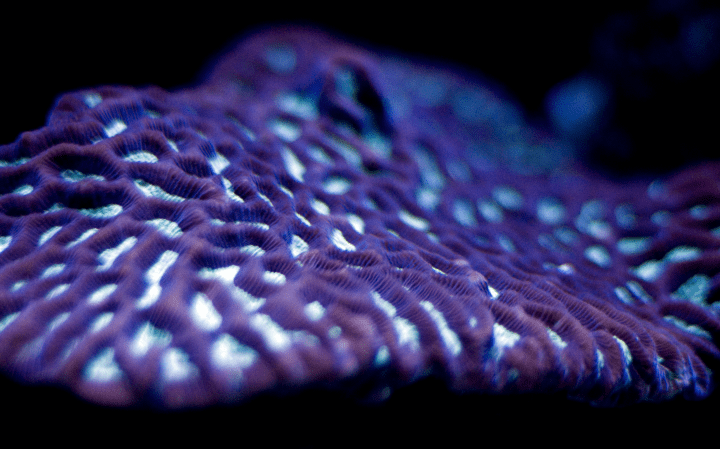

Halophytes, or salt-tolerant plants, are found in a number of environments: seashores, mangrove swamps, salt marshes, and saline semi-deserts. As the amount of salt in agricultural soils increases, it’s important to understand how different plants cope with salt, a mechanism known as salt tolerance.

Some plants are much more tolerant of salt than others. Many of the crops we use in agriculture, such as wheat, rice, and corn, have a very low salt tolerance, although their wild relatives (non-domesticated species that are closely-related to food crops) are oftentimes much more tolerant. So, why haven’t food crops evolved to adopt this tolerance?

It is hypothesized that that salt tolerance is an “evolutionary labile” trait, which means that it is less correlated with other traits and therefore doesn’t face the same evolutionary “pressures” that would require it to be expressed in each generation. These traits often vary widely in how they are expressed between individuals and between related groups of organisms. Another way to think of labile traits is that they are not “locked in” within evolutionary lineages. Some examples of evolutionary labile traits are reproductive timing and migration timing. This is in contrast to non-labile traits, which are much more ‘constrained’ by evolution and are less likely to change, for example, leaf size and color.

Preserving wild relatives of food crops allows us to study and understand how salt tolerance has evolved in different species. As sites of both public engagement and plant conservation, botanical gardens are working to educate the public on the value of conserving a variety of different plant species. You can learn more by reading this open-access chapter on Public Education and Outreach Opportunities for Crop Wild Relatives in North America, co-authored by UBC Botanical Garden’s Dr. Tara Moreau.

Adapted from the UBC Botanical Garden “Botany Photo of the Day“