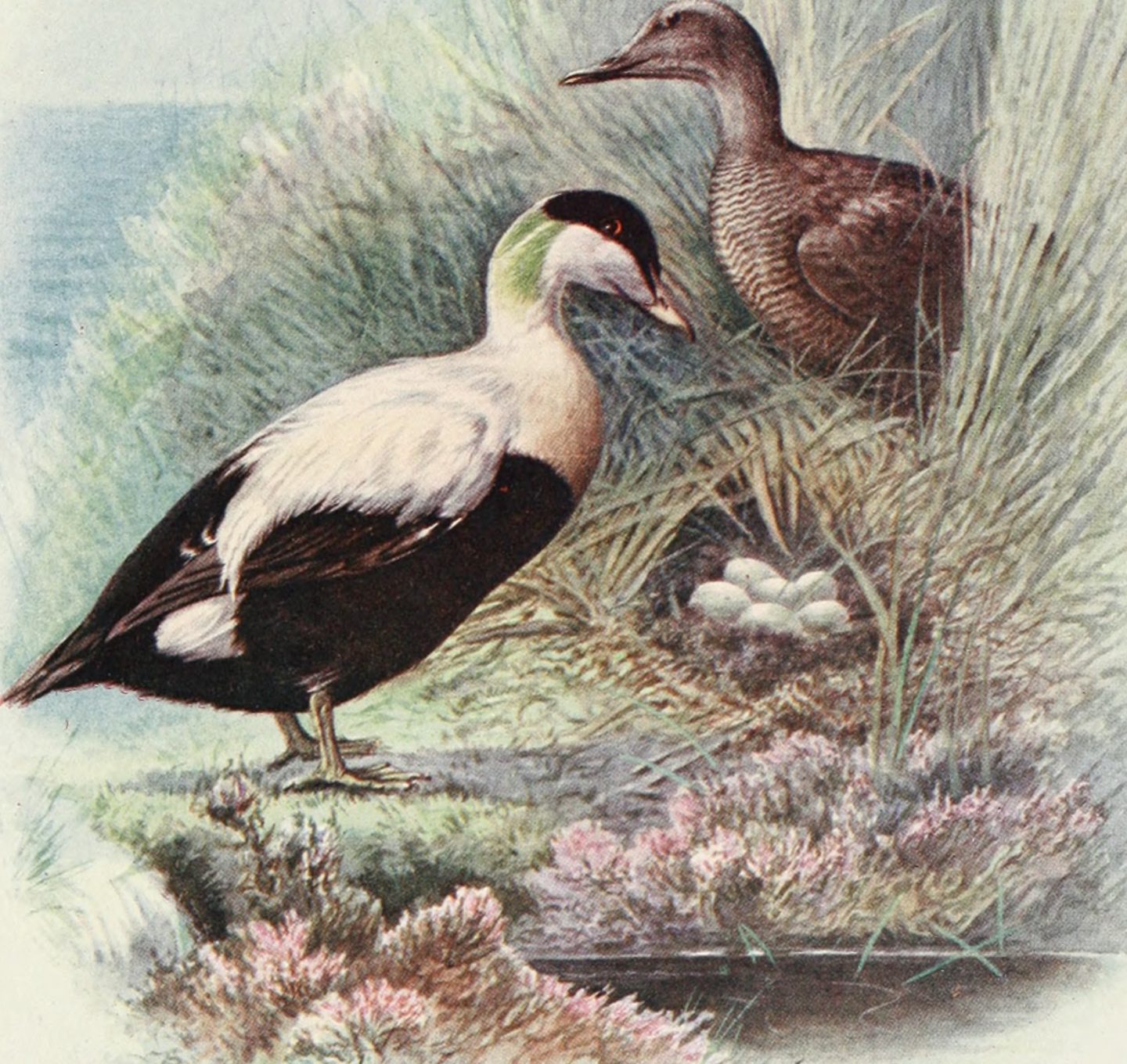

The bigger barbules and higher number of microscopic prongs on the down of eider ducks trap more heat than other feathers.

Introduction

If you’ve ever braved winter weather in a down jacket or snuggled under a down-filled duvet, you may have wondered: What’s up with down? How can a material that’s literally as light as a feather provide such warmth? The secret is in the structure. And a close look at a down feather reveals how it works.

The Strategy

Typical outer feathers, like the ones quill pens were made of, don’t have this insulating effect. They have a firm central trunk called a rachis. Stiff shafts called barbs jut diagonally off the rachis to the left and right like branches. The barbs have smaller structures branching off of them called barbules. The barbules have tiny hooks called prongs that grab adjacent barbules, keeping them closely interlocked and aligned. The whole feather structure is basically straight and flat. That makes them great for flying or keeping out water, but not much good for retaining heat.

Down feathers, in contrast, have a short rachis that looks more like a stem than a trunk. Long barbs extend out of the top. But unlike outer-feather barbs, down barbs aren’t stiff. They are soft and flexible, as are their barbules. They billow out in all directions and overlap to form fluffy spheres. Each barbule is more than 10 times thinner than a strand of human hair, but a single feather may contain miles of them.

The wispy spheres are ideally shaped to splay out and clump together. They fill up empty spaces where air could pass through. They create a cohesive barrier that traps in an insulating layer of air. The down also blocks cold winds from sweeping away the bird’s heat. Because the feathers are flexible, they don’t break when they are compressed, and they quickly fluff out again.

The feathers of other types of ducks and geese have similar features. But zoom into the down of eider ducks, and you’ll see what puts it in a class of its own.

Eider ducks live and nest along the most northern coastlines on Earth. They need to keep warm as they forage for food in icy waters. Beneath their waterproof outer feathers, a layer of down traps heat just the way a down vest does for us. Back on land, they need to protect their eggs from frigid temperatures and fierce winds. This, too, they do with down. Adults pluck down feathers from their breasts to cushion and insulate their nests.

For these high-performance needs, eiders have developed barbules on their down that are bigger than those of other ducks or geese, so they fill more gaps. Their barbules have more prongs near their tips, and the prongs are shaped like tridents, rather than the two-tine prongs of other birds, so they stick together better. Like tent poles, they keep the ends of the barbules from flying outward, maintaining a heat-trapping tent-like shape. These extra features make eider down feathers even more cohesive and warm—a necessity for living and breeding in the harsh arctic conditions.

The Potential

Because down is insulating, light, and compressible, it is an ideal material to make warm jackets, vests, gloves, sleeping bags, and quilts. Revealing the microscopic structures and mechanisms that give eider down its remarkable properties can show people ways to develop synthetic insulating materials that mimic what feathers do naturally.