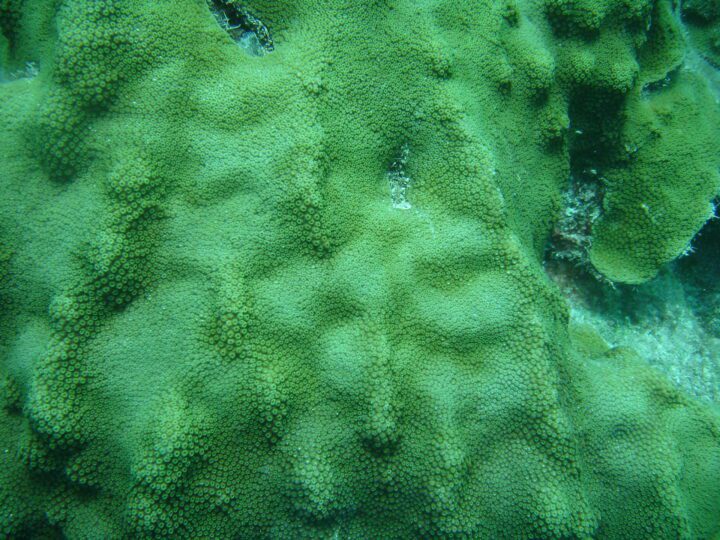

Individual scales of pangolins with complex layering overlap to create a flexible shield.

Introduction

Tucked safely into a ball, impervious to the teeth and claws of an inquisitive lion cub, a pangolin seems to make survival look simple.

Members of this family though, which live in tropical parts of Africa and Asia, are literally among the toughest prey animals around. Except for their bellies, pangolins are covered with thick, overlapping scales made out of keratin, the same material that makes up human hair and fingernails.

Watch a young lioness test a pangolin's defenses.

The Strategy

When not threatened, a pangolin spends its time burrowing in the ground or climbing in the trees foraging for ants and other insects. But when a predator appears, it curls up into a tight ball. The curved body causes the sharp edges of the scales to stick out. And the scales’ virtually impenetrable nature prevents teeth and claws from getting to the juicy parts inside.

Pangolin scales have a number of traits that help them provide strong and durable protection for their owner.

Starting at the micro-level, they are made up of three distinct layers of flat, elliptical keratin-rich cells. On the bottom (ventral) layer of each scale, the cells lie parallel to the surface in sheets that overlap. In the thick middle (intermediate) layer, the cells tilt up at about a 45-degree angle. In the thin top (dorsal) layer, they tilt up more rapidly and completely fold over until they’re almost parallel to the bottom layer again, now running in the opposite direction. The combination of flat, tough, overlapping layers of cells with diverse orientations creates a structure that is hard to puncture but also absorbs the force of an attack. It is virtually impossible to shred, and readily stops a crack in its tracks if one starts to form. Not only that, but a threadlike substance stitches the flattened cells together, making it hard to separate the individual cells and layers one from another.

On a macro-scale, the scales are modular and overlap enough that they allow the animal to curl up without stretching or exposing bare spots of skin between the plates of its armor. They continue to grow throughout the pangolin’s life (much like our hair and skin) so they can continue to protect the animal throughout its life despite any wear that takes place. They have a corrugated outer surface, so they slide smoothly against each other and against soil or other substances. And if a predator dents the coat of armor while trying to get through, the pangolin can repair the scales after the attack by simply wetting itself down and letting its scales absorb water to balloon back to their original shape.

The combination of flat, tough, overlapping layers of cells with diverse orientations creates a structure that is hard to puncture but also absorbs the force of an attack.

The Potential

Pangolin scales already are being tapped by researchers studying better ways to make armor for battlefield uses. Their anti-friction, anti-stick properties have inspired the design of a surgical knife that separates cleanly from the tissue it’s cutting through. Other applications of the pangolin’s unique approach to self-protection could include anything from more durable sofa cushions to buildings and bridges that not only withstand storms better than their conventional counterparts, but also repair themselves when they do incur damage.

While these innovations all draw from the design and function of pangolin scales, and cause no harm to the animals themselves, traditional Chinese medicine puts a high value on human consumption of the scales themselves. Pangolins are hunted, killed, and their scales ground into powder. The demand is so great that all eight pangolin species are now threatened with extinction.