Far more than just flight aids or decoration, feathers take a simple form and iterate upon it to serve countless functions and benefits for birds.

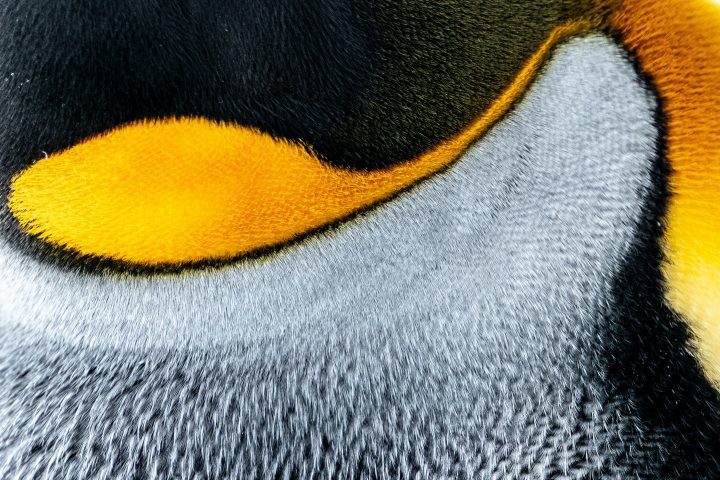

If you open the cabinets in the ornithology department of a natural history museum you would see thousands of specimens from species across the avian evolutionary tree. When I look at the incredible diversity displayed in these specimens, I am first and foremost struck by their feathers. Feathers are different sizes and shapes depending on the type of bird, but as an artist as well as a scientist, the variety of colors and patterns immediately catches my attention. Upon closer inspection, what appears at first to be a virtually endless color palette slowly resolves into repeatable patterns – certain families of birds might tend to be colorful or drab; species from certain parts of the world might be more likely to display certain colors or patterns; males, females, and juvenile birds might tend to have typical appearances. Connecting these observations with species’ behaviors, environment, or life histories can help scientists elucidate functions of these colors, and link these functions to the types of feathers that produce them.

Consistent trends might give hints as to the underlying forces of natural selection and evolution that have produced the patterns we observe today. For example, flight feathers on wings tend to be under the most constraint in flighted species, so the possible variation in these feathers is extremely limited (Kiat and O’Connor 2024). Conversely, body feathers, which are responsible for many functions (e.g., visual communication, thermoregulation, and waterproofing), can vary in size, structure, color, and composition (Terrill and Shultz 2023).

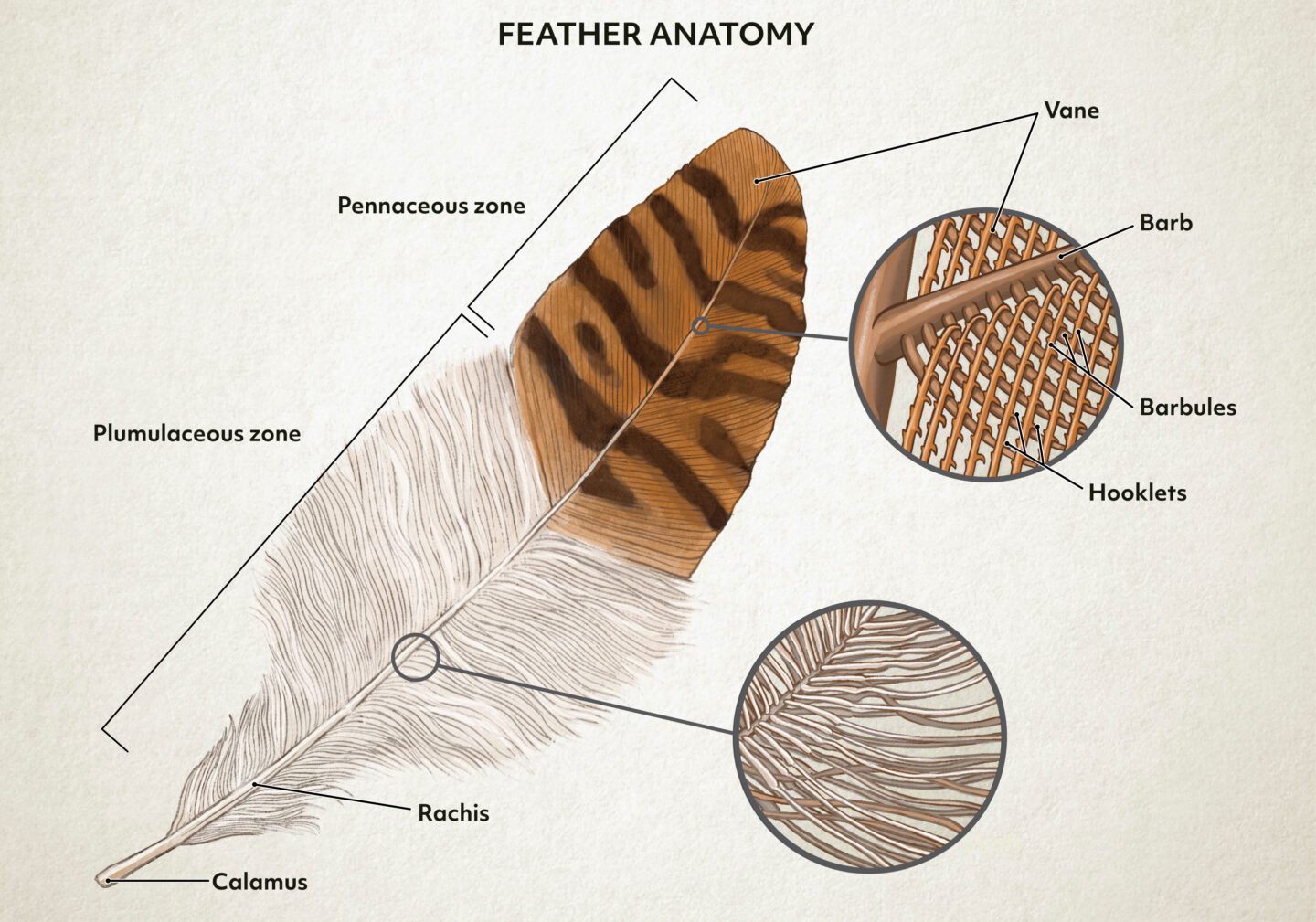

Feathers are modified forms of a basic structure that accommodate the diversity of functions they perform. A basic feather consists of a central rachis, analogous to the trunk of a tree, with microstructures analogous to branches extending out on two sides, called barbs, which have additional microstructures analogous to twigs attached to either side of the barb, called barbules. Together, these barbs and barbules create uniform surfaces in a single plane, termed feather vanes. Even smaller structures attached to the barbules called barbicels or hooklets attach to adjoining barbules like a zipper, ensuring that structurally important features can keep their shape. The earliest feathers, which likely evolved from archosaur scales prior to birds, consisted of only an undifferentiated cylinder, and likely evolved in a stepwise manner to become more complex and produce the diversity of structures we observe today (Prum 1999; Wu et al., 2017).

The basic feather structure can be modified to perform different functions, across the body of a bird or across species. Wing feathers typically have little variation in the shapes of the microstructures, and have structurally-sound asymmetrical vanes, making each feather an efficient airfoil (Lucas and Stettenheim 1972). Tail feathers are also constrained for flight with symmetrical vanes. Contour feathers have two sections, one that is closer (proximal) to the body, termed the downy section, and one further away from the body, termed the pennaceous section. Variation in feather size, length, shapes, or these proportions can be thought of as variation in feather macrostructure. Downy parts of the feather tend to have no hooklets and longer barbules, and a much looser structure, and the pennaceous parts of the feather that is exposed to outside air exhibits most of the observable variation in color and microstructure (sometimes having barbules and hooklets, sometimes not). Other specialized feathers might include those with a very loose structure called semiplumes, no central rachis and only loose barbs, called down, or a central rachis with only a few barbs at the very top or bottom, called filoplumes and bristles, respectively. Filoplumes and bristles play important sensory roles, either sensing the positions of feathers or the environment, respectively, similar to mammal whiskers (Lucas and Stettenheim 1972; Rohwer et al. 2021).

Understanding how feather macrostructures, microstructures, even finer-scale nanostructures (e.g., internal structure in feather barbs that produce blue colors or iridescent colors) and pigments together produce the diversity of feather functions requires a combination of biological insight, engineering, and chemistry. For example, birds can combine nanostructures and pigments to enhance their available color palettes, or modify barb and barbule shapes to either make feathers darker or brighter, and enhance the colors of underlying pigments (McCoy et al. 2021). The loose structure of down is responsible for providing insulation, and variation in microstructures or macrostructures (Barve et al. 2021) can enhance the thermoregulatory potential of these feathers. Despite this structural variation, feathers are universally composed of beta-keratins (different than the alpha-keratins that make mammalian hair), and functional variation is a result of structural variation over variation in materials (Bachmann et al., 2012).

Video: How do feather barbules attach?

In this short video Janine Benyus describes the structure and function of feather barbules.

Feathers are structures that must accomplish many different functions simultaneously, and modifying part of a feather for one function may change its ability to perform a different one. When I look at the beautiful reds, yellows and blues found in the feathers of many species, especially in males seeking to attract females, I can’t help but wonder at the disadvantages they experience as a result of these flashy hues. For example, feather microstructures are responsible for making a feather waterproof, and modifying microstructures for other reasons, for example, to produce iridescent colors, can decrease the ability to repel water (Eliason and Shawkey 2011). So any study considering how feather form might be related to one function must consider the push and pull of those same forms for other functions. As an artist, I explore the tension this creates, and for example by incorporating color palettes not only from the colorful males, but also by the drabber females. Additionally, feathers can be studied as single structures, but work together to form continuous surfaces, which is important for a variety of functions, like capturing warmth or being waterproof. Feathers also only exist in the context of the other underlying body structures. For example, flight feathers in birds that spend a long time gliding complement long, thin bones and are shaped to produce long, skinny wings, and flight feathers in birds that must be very maneuverable tend to complement shorter, broader bones to produce rounded, curved wings.

The variety of forms and functions observed in feathers provides inspiration for artists and engineers, for example inspiring new ways to produce long-lasting, non-toxic printed colors (Echeverri et al. 2020; Hu et al. 2021). But, observations from nature hold tremendous potential for additional biomimetic applications. Recently described specialized feathers from sandgrouse are super absorbent, and could have a wide range of applications from medical-grade sponges to sponges for soaking up oil spills. Superblack feather structures absorb more light than alone (McCoy et al. 2018), and could inspire new textiles or specialized paints. Seemingly endless possibilities exist to draw inspiration from feathers to produce new technologies. Knowing this, when I look at specimens in our collection or see birds in my neighborhood, I pay close attention––how do feathers vary across their bodies and how do they use them, or even how do color patterns change across life stages or throughout the year. Some of my most exciting projects started out because I was curious about why a bird looked a certain way, but ultimately could lead to technological innovation.