Before beginning their current voyage around the entire Pacific Ocean, the Polynesian voyaging canoes, Hōkūleʻa and Hikianalia, sailed in 2022 to Hawaiʻi’s ancestral homeland of Tahiti. Navigator Lehua Kamalu shared these thoughts as the team made final preparations for the journey.

This voyage will focus on navigational training and significant cultural protocol to prepare our crew and test the canoes before we embark on a much longer journey next year––a circumnavigation of the Pacific.

The course we take is completely commanded by nature. But nature takes the canoe along a very specific pathway.

We even have a word for it, Kealaikahiki, which literally means “the pathway to Tahiti.” It’s as much of a paved highway as you can possibly think of on the ocean, where the weather comes together to allow you just enough time, just enough space, to make the journey successfully. And we think about all the natural elements––birds and their flight patterns, fish and marine mammal populations that have been known in the same place for generations––all of those elements contribute to this being an actual sea road. All the right pieces are here to show you where to go.

It’s funny that we think “there’s nothing out there.” There’s so much out there.

Finding Islands

The islands we’re trying to find are not tall. Tahiti itself is a very tall island. But the islands that you find first when sailing from Hawaiʻi are low-lying atolls whose highest point of elevation are the tops of the coconut trees that sit on them. You cannot see those coconut trees from far off shore. You’re going to be within four to eight miles (six to twelve kilometers) when they become visible.

You have to learn to see the island by seeing all the signs that the island is there. That can be the birds, the colors in the sky, the clouds, the wave patterns that have changed because they are affected by the island and you as a navigator can notice it.

The animals themselves are always the ones that you have a really strong connection to. They’re animated, they’re the life that you see out in the water and above the water. Manu-o-Ku, the fairy tern, is such an important one. That’s firstly because there are many of them, but also because they stay within a range of about 50 to 100 miles (80 to 160 kilometers) from an island. And they return home at night. I think of birds and clouds as going to work in the morning and coming home at night. And because of that, you can follow the rush-hour traffic back to the island that they came from.

By having creatures like manu-o-Ku on these islands, I think you have to redefine what the edge of an island is and realize that the birds take that edge out farther into the ocean for you. They become that leading edge.

For other birds, such as the albatrosses that you can find out at sea, you need to know that those are not going to take you to an island at the end of the day. You can follow them around for four years, and they’ll probably just take you in circles.

So birds always come to mind first for me when we’re thinking about the island we’re going to. I feel like I can never say that I’m navigating to it. It’s really them navigating to it. They’re the ones who have this incredible internalized GPS that lets them find islands without seeing them. I’m just trying to keep my eyes open long enough to see where they are and what they’re doing.

You have to redefine what the edge of an island is, and realize that the birds take that edge out farther into the ocean for you.

On this particular journey to Tahiti, there are pods of dolphins that are recorded in certain places that they say are always in that particular place. Master navigator Mau Piailug recorded it back when they did the original Hōkūleʻa voyage in ’76. I believe it was recorded again a number of years later on. These are just known regions where marine mammals stay.

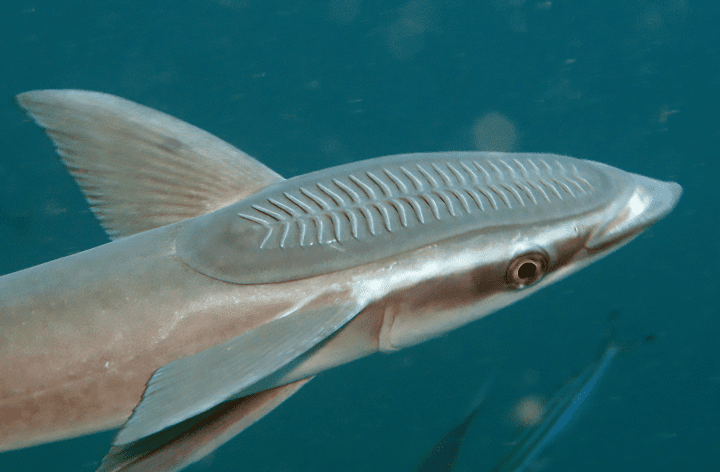

Some folks like to take note of fishes that tend to stay near land as well. Sometimes you see them, sometimes you catch them. So I find the creatures are pretty critical once you’re landing the island itself, or departing it.

On the Open Ocean

But when we’re going between islands themselves, a lot of what you’re paying attention to is the living creature that I’d say is the ocean itself, and its many different facets and characteristics.

Those are the things that you’re really tuned into––the periodic motion of the waves and comparing that to the pattern of the wind. And then of course, there are the endless cycles of the celestial bodies above. All of these things are signs, and as Pwo Navigator, Nainoa Thompson says, you’re going to pay attention to 5000 signs from nature every day.

I’m thinking about how high the sun is in the sky, where it rose, how does it hit total zenith above my head? Is the moon going to be up during the daytime or the nighttime? Am I going to have a dark sky? What stars am I going to be able to see that night? I’m calibrating the position of the canoe with those things as really fixed points, but also with the ever changing nature of the ocean and the wind above it.

So, there’s a lot out there.

The challenge is actually figuring out what to pay attention to. So for me, the birds and other animals are the gifts from the gods, saying, “hey, by the way, while you’re trying to figure out that super complex system of weather patterns and the ocean, I’m a bird who happens to know exactly where you’re going. And you can just follow me this way and it’ll be a lot easier for you.” And I think, “Oh, yes, thank goodness.”

I haven't thought of a way that you can [use traditional navigation] without these natural elements and these birds and these other creatures being there to show you the way.

The Future of Navigating

When you think about how connected we are to the birds, connection doesn’t even describe it. For me, I feel 100% reliant on them. If that bird doesn’t show up, maybe I still find the island, but also maybe I don’t. If the bird shows up: I know we will. It’s impossible to do without them. When they’re not there, you really start to feel a concern.

Sometimes I wonder, were there supposed to be more birds on this island? More fish in this area that would help us find it? I think about this especially as voyaging and navigation evolve.

We know that we’re having an impact on the natural world, and that the environment that allows these animals to thrive is the environment of the navigator. Without that, I would say navigation becomes almost impossible. I haven’t thought of a way that you can do it without these natural elements and these birds and these other creatures being there to show you the way.

We are simply there to listen, to observe, to understand what we’re looking for, to learn to figure out what we’re looking for.

In what way can we make sure that they will still be there showing us the way?

The Moananuiākea Voyage

The voyage to Tahiti is a prelude to a much longer journey to come––a circumnavigation of the Pacific to begin in 2023.

Sense of Peace

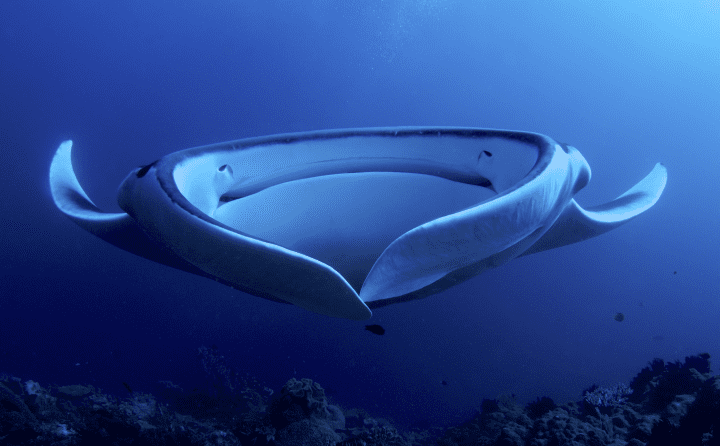

We have such a great privilege in being near the bottlenose dolphins that are following us, or the humpback whales, the false killer whales, the manta rays, all these creatures. It’s not like being humans visiting a zoo. The animals are not on display for us, we are part of them. And if we see ourselves within that system, I think we change our minds a little bit about what we are doing, what we’re not doing. We find that space to be quiet and to be focused and to be connected and to be completely reliant on nature.

Still, I like to think that everyone that would see these things would have the same sort of feeling and reaction to seeing them: excitement, wonder, an incredible sense of peace to see something alive and active and thriving in their environment.

When we’re on the ocean, there’s not a lot of safety nets, there’s not a lot of creature comforts. You get to be out there in the elements, and maybe in some ways, when you do that, you get to be more human than you are on land.

I want everyone to have that experience of being in an environment where you feel I’m connected to nature, I’m part of it, I have a role in it––and so does every other human. When you start to see other people in that natural space as well––just as powerful, just as inspiring, just as capable of finding peace in the world as those dolphins and other creatures––it helps to direct you in a much more peaceful, harmonious state. It’s never helpful to be angry all the time about the state of the world.

By Lehua Kamalu, as told to AskNature.

The Collection

The peopling of the Pacific has relied strongly on a knowledge of, respect for, and partnership with the non-human creatures already calling this vast ocean home. The fragility of our human populations require that we live in harmony with our surroundings not only on epic open-ocean voyages, but also when establishing our own homes here. It hasn’t always been perfect harmony, but the deep value of understanding and cooperation with the rest of nature has enabled humans to survive and thrive in this unique environment.

The other creatures of the Pacific offer much we as humans everywhere can learn from, in every dimension of human endeavor. From our relatively close relatives, the marine mammals, to the mollusks and others our lineage branched off from hundreds of millions of years ago, we can draw countless lessons, examples, and inspiration. Explore below some of the intriguing adaptations they have made, and see if you can navigate to new thinking for addressing the challenges you are in a position to meet.